Amy Karle &

THE SMITHSONIAN

Regeneration Through Technology

Leveraging Smithsonian 3D scan data of a fossilized Triceratops skeleton as the basis of inquiry into the past, present, and future, Artist Amy Karle’s artworks made in collaboration with The Smithsonian Institution’s Museum of Natural History and Digitization Program Office and exhibited in conjunction with the launch of the Smithsonian Open Access Initiative contemplate how technology can not only be used to capture and study form, but also impact evolution. The research and nine resulting sculptures present possibilities of reconstructive technologies, exploring potentials and pitfalls of future evolution through technological advancements.

The basis for this collection by Amy Karle is “Hatcher”, a 66-million-year-old Triceratops skeleton in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History who made history as the first “digital dinosaur”. The original fossil display from 1905 consisted of bones from ten different animals. In 1998, curators created a more accurate computer-assisted cast by 3D scanning the fossil and manipulating the bones in the digital environment to correct scale. This was the first 3D scan of an entire dinosaur skeleton.

22 years later, in the context of cutting-edge digital, biotechnological, computational and additive manufacturing developments, Amy Karle expands on Hatcher’s legacy by opening an inquiry into what representation and composite with computer-assisted technology means for us now and into the future. She leverages this technology in both her research and as tools in the process of creating the final artworks for this collaboration.

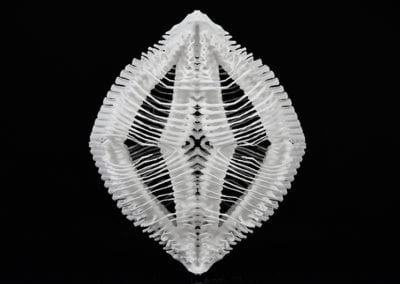

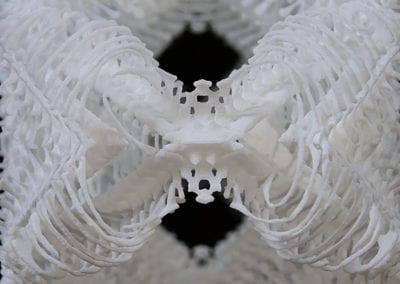

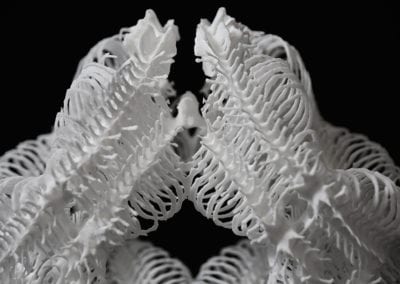

MORPHOLOGIES OF RESURRECTION

(series of 6 sculptures), 2020

biocompatible polyamide, glass, wood, brass

How can we use information from the past, including that of extinct species, to learn about form and function to create new forms and organisms that could potentially heal and enhance our bodies, environment and various species?

Designed from portions extracted from the spine of the Smithsonian Institution’s 3D scan data of a Triceratops fossil, Morphologies of Resurrection imagines new forms based on extinct species, depicting hypothetical evolutions through technological regeneration. The six finely detailed sculptures are presented as both specimens and relics to reinforce that the possibilities and limitations of reconstructive morphologies and enhancement through evolutionary technology as something to be studied and researched; as well as to be contemplated with veneration, as the use of such technology can permanently alter evolution and various species, including humanity.

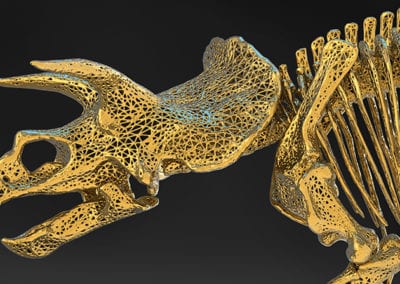

DEEP TIME AND THE FAR FUTURE

(series of 3 sculptures), 2020

biocompatible polyamide, gold, copper, silver, paint

Extinction seems so finite, but is it?

“Scan data” is not just about capturing images or forms, it can also include capturing biological data such as DNA and include processes such as machine learning and Artificial Intelligence. With such tools, we now possess the potential to remake, reconfigure, even revitalize old forms … but is this wise? Resurrecting extinct species could shed light on how ancient creatures lived, died and evolved and offer insight into how to enhance species to survive and thrive in the future… but could also lead to unforeseen consequences.

Manufactured alterations can implement drastic change far faster than natural evolution. With the advance of genetic modification, machine intelligence, and drastic environmental pressures, future evolution will proceed at a greatly accelerated rate. Deep Time and The Far Future explores the relationship between reconstructing the past and the importance of a deeper awareness of the long view of time in this process.

Technologies have led to extinction and can lead to de-extinction. Due to the current limits of our technology and of DNA survival, de-extinction of Triceratops, which lived 68 to 66 million years ago, is not a possibility at this time. However, de-extinction of other species is a closer reality with scientists actively researching in this field. In such cases the result would not be a clone, but a hybrid including the DNA of the extinct species with that of related living species.

This idea of creating a new species by partially rebirthing an extinct species is an especially intriguing and fascinating aspect that appears in the artist’s work, leaving a sense of what was and the chance of a new synthesis. As Karle works through these concepts, intermittent variations become clarified through technological and studio practice, and the prospect of new realities emerge in a multi-layered way.

The sculptures of Deep Time and The Far Future are finely detailed in cellular and scaffold patterns mimicking those which could be used for cell culture made through additive manufacturing in biocompatible materials. Specimen No 1 and No 2 are presented in gold and silver as a reminder to contemplate such prospects with precious regard; and No 3 in stratifications of angular unconformity to reflect the stratum of deep time.

An investigation into representations and depictions and ideas that can only be realized through such technologies reflects on the closely related subjects of archive and relationship to the present also appear in this process, resulting in an examination of both the human search for conclusive stories and the question whether anecdotes fictionalize history.

The cast Hatcher, the Triceratops in the “Deep Time” exhibition at the National Museum of Natural History’s new Fossil Hall is posed in death. Amy Karle’s artwork presents the Triceratops standing, often peering into its own reflection or shadow, reflecting on potentials of how we may bring to life these extinct species of the past.

A VERY SPECIAL THANK YOU TO:

The Smithsonian Institution, The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, The Smithsonian Digitization Program Office, Smithsonian Open Access, HP and HP Labs, and to all those whose generous support made this project possible.